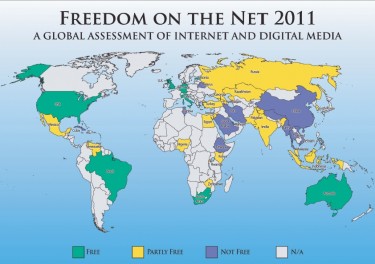

In the report (authored by Global Voices’ Alexey Sidorenko, editor of RuNet Echo), Russia is rated among those countries with “partial freedom” of Internet access. Compared with the organisation’s previous report, published in 2009, Russia’s position in the ratings has dropped.

Among Russia’s neighbours on the list of “partly free” countries are Rwanda, Zimbabwe and Egypt. Of the republics of the former USSR, Freedom House experts identified Georgia, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, along with Russia, as “partly free.” Belarus appears on the “not free” list, while Estonia is on the “free” list – in fact, Estonia tops the rankings for all countries mentioned in the report. Russia’s other former Soviet neighbours are absent from the rankings.

Trailing the field on Freedom House’s list are Cuba, Burma and Iran, where experts registered the worst situation regarding Internet freedom.

One cannot argue with the facts listed in the report about Russia. All the same, questions arise about their analysis and interpretation.

The first important question: What aspects of this ranking really originate with the authorities or state structures? What exactly is the Russian authorities’ contribution to “Internet unfreedom?” After all, it is generally accepted that the restriction of freedom be considered in terms of its usefulness to the authorities’ policies and functioning of legislation.

If we look carefully at the list, we will see two obvious types of actions emanating from state structures:

“E-Centres” to prosecute extremists

1. The activities of law enforcement agencies and units within the fight against extremism (so-called “E-Centres”), which actually direct the prosecution of bloggers (and not only bloggers) for expressing opinions on the Internet. More often than not, cases are brought according to Article 282 of the Penal Code; specifically according to Part 1, which includes penalties for “activities, carried out in public or via media, aimed at the incitement of hatred or hostility or the degradation of a person or group of persons on grounds of gender, race, nationality, language, origin, religious inclination, or membership in a particular social group.”

I have explained more than once how this mechanism works. E-Centres are the operational units of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) in every Russian region. They carry out the functions of the MIA in the area of counter-extremism. These units have a “top-down” plan for the fight against extremism: a certain number of citizens over a certain period of time must be held accountable for extremist activity.

Where do E-Centres look for extremists? Seeking out those who are plotting “the formation of extremist organisations” or some other kind of extremist activity is difficult: for that you need to have informants to carry out quality surveillance over a long period and collect information and evidence. That’s difficult. It is easier to find “extremists” on the Internet while sitting at a computer in your office, reading blogs and forums and looking for sharp, critical opinions of authorities or some social group or other.

It’s a cushy job: find a statement and, if its author is somehow identified, turn your attention toward the Internet service provider to find out whose computer the message was sent from. That’s it. An extremist is rooted out, the task is carried out, the question is closed, the bosses are happy, a report on the “fight against extremism” is dispatched to Moscow, and the bill for its foot soldiers continues to be paid from the state budget.

That is precisely why the Russian Internet community and human rights activists must fight for the abolition of Article 282 of the Penal Code of the Russian Federation. As law enforcement practices demonstrate, just about anybody can fall into the category of “extremist:” bloggers, Internet users, writers, community activists, religious figures, whoever you like, only to justify the existence of E-Centres, which previously, by the way, were “Units for the Fight Against Organised Crime” and have retained their practice of meeting quotas. It is also necessary, in my opinion, that Centres for the Fight Against Extremism close, since they are involved in activities that are beyond their remit: in reality, they prosecute the free expression of opinions, be they political or religious views.

As regards the prosecution of bloggers, the real reason behind it is often not a statement by a given person on a blog or on the Internet, but instead his or her other activities (social, political or commercial). The expression of an opinion on the Internet acts only as a convenient pretext for the initiation of pressure or prosecution.

Blocking Internet resources

2. The second action emanating from the state and directed “against the Internet” involves the judicial system, which, at the instigation of the public prosecutor’s office, can decide to block Internet resources. Yes, indeed, the court in Komsomolsk-na-Amur city made an utterly illogical legal decision to shut off users’ access to YouTube because the site allegedly hosts extremist materials. Later on, the court of appeal overturned this decision, identifying specific pages on the site to which access must be blocked by Internet service providers. Well-known Russian internet activist Anton Nosik then wrote on his blog [ru]:

By the level of its crudeness, the court’s verdict is typical of all domestic legal proceedings concerning the Internet.” These happenings are, in Nosik’s opinion, “All in all, only an amusing legal episode that is of no practical consequence for tens of millions of Internet users in Russia.

The number of ignorant decisions taken by Russian courts is well known to all, and they do not only concern the Internet. This area is one the majority of judges and prosecutors do not understand; they tend to confuse sites maintained by their owners with services or sites based on user-generated content (UGC).

Ignorance in relation to the realities of the Internet, however, is not particular to the activities of judges and prosecutors alone. Not long ago, a businessman asked a friend who the “editor-in-chief of Twitter” was, and whether it would be possible to meet him. People’s general ignorance regarding the realities of the Internet leads to such episodes.

The conclusion here is simple: a movement focused on rectifying this lack of awareness is required, so that rulings about “YouTube shutdown” provoke not only the indignation of users but also the hearty laughter of the Internet community that believes an actual YouTube shutdown will not come to pass.

Untraceable control

As for the remaining facts contained in the Freedom House report, they may bear no relation whatsoever to the state and the authorities’ actions – or may, indirectly. DDoS (Distributed Denial-of-Service) attacks, which in recent times threatened LiveJournal.com and the Novaya Gazeta website cannot be linked to the state but result from either commercial orders or the unauthorised activities of certain individuals. The same goes for the hacking of certain sites by the “Hell Brigade.”

Activity in the blogosphere by “pro-Kremlin youth organisations” is more a positive than a negative fact, reflecting real freedom of expression by political forces of different stripes. There is evidence of both liberal and nationalist activity in the blogosphere: those for Putin, and those against him; those for Stalin, and those against him; those for Khodorkovsky, and those against him.

The means of conducting the discussion are, admittedly, not always good: there are trolling and spamming and ad hominem attacks. But these complaints can be laid against anybody, not just against “pro-Kremlin forces.” The thing is, depending on the topic, distinct groups are mobilised differently, so that in certain discussions (indeed, those that have to do with topics such as Stalin, Yeltsin, Khodorkovsky, the Russian Orthodox church and others) the better mobilised groups take part in discussions with greater aggression and fury.

Of course, the purchase of successful services and websites by businessmen close to the Kremlin can, to a certain extent, be put down to “state influence.” But it seems to me that we are dealing in these cases with the usual desire in business to acquire a commercially successful venture.

Moreover, it is difficult to cite an example of owners influencing the editorial line of Lenta.ru or the ‘editorial’ policy of LiveJournal. Blogs on LiveJournal are completely free, and a recent period when the site was down could be attributable not only to a DDoS attack, but also to unresolved technical problems on the part of the service itself. Another important factor is a statement by President Medvedev, who drew attention to the attacks on the popular blog hosting service and condemned them. The president coming to the defence of a popular blog hosting service has no precedent in any country.

Yet it is still worth remembering the Kremlin’s tough position regarding the Federal Security Service’s (FSB) initiative to ban access to Skype, Gmail and Hotmail, about which I have written in a previous article. The truth is, yet another initiative of the Russian government came to light a few days later: a tender to carry out research into the foreign experience of regulating responsibility for Internet networks. The research should analyse the legislation of the USA, Germany, France, the UK and Canada, as well as China, Belarus and Kazakhstan where, as we know, the Internet is blocked.

On the whole, my conclusion regarding the situation of the Internet in Russia, as described in the report “Freedom on the Net 2011,” is as follows: yes, Russia can be included among those countries with “partly free” Internet access. At the same time, this particular lack of freedom is not due to the deliberate policies of the federal authorities. At least for the time being, the authorities are not seeking to limit Internet freedom, and Medvedev’s position on this matter is clear enough. Only Article 282 of the Penal Code and the activities of the “Centres for the Fight against Extremism” raise a real concern.

Notwithstanding this, not only Internet users but human rights defenders, political activists, historians, religious figures and other “troublemakers” suffer. The Internet here is but a pretext for accusation. Ignorant judges and prosecutors are trouble too – not only in terms of the Internet but sometimes in terms of legislation in general, which they themselves do not understand or interpret terribly. Yet another real problem is that in Russia we are dealing with a multitude of actors who may engage in violence against bloggers and activists. This multitude can appear to be an integrated instrument of the authoritarian state but, if we look closely, it reveals itself as a vector resulting from the actions of various security agents, bureaucrats and bandits.

Therefore, to “liberate” the Internet and raise Russia’s position in Freedom House’s ratings, the Russian community must turn its attention to Article 282 and start a campaign to have it repealed. This is well within the power of the Russian Internet community.

· Translated by Catherine Lawlor

Originally Published at GlobalVoices: http://globalvoicesonline.org/2011/05/03/russia-who-is-restricting-the-russian-internet/

Leave Your Comments